50 Years of Text Games: from Oregon Trail to AI Dungeon

By Aaron A. Reed

620 pages, text with B&W illustrations $25 (e-Book)

Like the earliest examples of books and film, the earliest computer games were defined by the limits of their technology. Games such as Tennis for Two (eventually re-envisioned as Pong) and Spacewar! used monochrome sprites that could be modulated via console-style controls; when graphics had to make the jump to home-based consoles, they became blocky and pixelated, recognizable only by the game’s title and box art.

Other games from the same era, however, took a different approach to evoking galaxy-spanning wars or epic fantasies. These games used a text-only interface that evoked their worlds through descriptions, interactive conversations, and player-driven exploration, with the user typing out instructions that the game would follow, respond to, or reject. Such games represented an extension of tabletop RPGs such as Dungeons and Dragons into the digital age—not just in the ways they played out, but also in their subject matter and vivid, immersive language. Due to the computational power required for such games, despite their text- and number-centered interfaces, they were for years only available on shared, centralized mainframes, often only accessible via university networks, where users played late at night to ensure their games would not be discovered and removed from the central mainframe.

It is in this fascinating era of clandestine computer-lab sessions, games shared on tape and disk, and a free-for-all approach to writing and game design that Aaron A. Reed’s 50 Years of Text Games kicks off. The book, which traces the history of text games through a half-century beginning in 1971 and culminating in 2020, takes the intentional approach of focusing on just one game per year over its half-century scope, which inevitably means hundreds of potentially discussion-worthy games appear only as footnotes. Some of these are major touchstones of the genre; others are lesser-known curiosities, or are, like 1979’s The Cave of Time, not computer games at all.

Reed, who alongside his role as a writer and scholar of gaming history is also an acclaimed game creator, fittingly lets the games’ stories—the ones they tell, and the broader stories around their development—speak for themselves:

These aren’t necessarily the most famous fifty games from these years, nor the best-loved, the most influential, or the most important (whatever that might mean). The constraint of picking one and only one game for each year instead suggests a grand tour, a journey that can’t possibly include everything but aims to stop at many interesting sites along the way.

At over 600 pages, the book could easily have been a mostly shelf-bound work of reference; instead, this unpredictability makes it imminently readable. And for those approaching the book as more of an off-the-shelf reference manual for text games as a whole, the lists of additional games in each decade’s introduction, as well as the extensive index, offer a comprehensive overview of the genre.

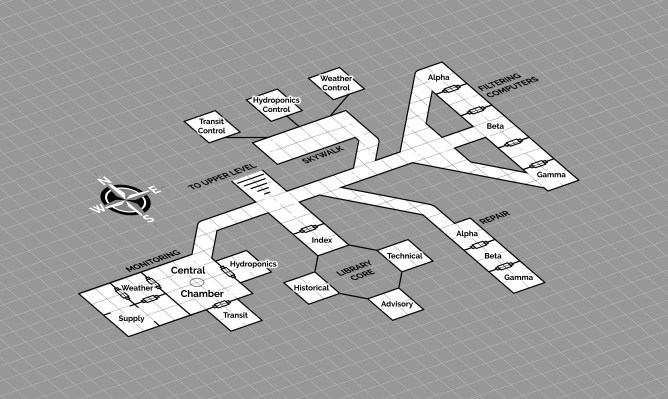

Lastly, while text-based games may not lend themselves to the colorful screenshots of their graphics-based counterparts, the book nonetheless offers a fascinating and surprisingly varied selection of images. These include screenshots from games discussed (generally limited to title screens or primitive ASCII graphics), maps of game worlds such as Adventure and Zork, game design documents and excerpts of code, and ephemera such as advertisements, manuals, and articles. Excerpts of text-based gameplay appear directly in the text, using distinct formatting to illustrate whether text is generated directly by the game or typed by the user. Marginal notes provide supplementary information and context, “links” to other chapters using a hyperlink-styled underline, and even provide shaded spoiler warnings for those who have not yet played through the game being discussed.

We asked Reed about his history in games, what sets text games apart, and where the genre might be going in the future:

While I imagine you’ve played text games for much of your life, when did you first start studying and writing about them?

I’ve been a lifelong player and even author of text games (recovered from my parents’ basement some years back was a hefty stack of handwritten-and-illustrated Choose Your Own Adventure pages I wrote in the fifth grade). In my twenties I thought about interactive fiction a lot from a design perspective as I got serious about writing my own, but when I went back to grad school it was specifically to study interactive narratives more deeply, both from the perspective of a maker and a theorist. In the course of researching the deep history of the idea of interactive storytelling for various papers (and eventually my dissertation), I got really enamored of this kind of research. I eventually co-authored a book about graphic adventures that was released in 2020 (Adventure Games: Playing the Outsider), which led to this new book about their textual cousins.

The crowdfunding campaign for the book topped out at over half a million dollars. While there’s clearly tremendous interest in the subject, were you surprised by this level of support?

I definitely was not expecting such an outpouring of support for the project: it became the second highest-funded nonfiction book project in Kickstarter history! (A record already beaten by this gloriously obsessive book about the history of computer keyboards). In hindsight, though, the success kind of makes sense: there are millions of people who grew up playing this genre of game that the mainstream has largely abandoned, and countless more who’ve discovered them in the decades since. And a book is such a great fit for a medium so focused on the joys of reading and the written word.

Since their earliest days, text-based games have included metatextual jokes and references. These go beyond allusions to reading and writing found in books like Tristram Shandy to reference the act of playing the game itself: typing, reading on a screen, or succeeding (or failing) to communicate with a parser. Later graphics-based games would similarly break the fourth wall (Metal Gear Solid, Inscryption), but this winking self-reference seems especially prevalent in text games. What do you think makes them so ripe for this kind of meta-narrative?

Text is such a wonderful medium because it literally inserts images directly into your imagination. Richard Bartle, co-creator of the original MUD (multi-user dungeon), has a great story that’s basically about imagining virtual reality tech getting better and better—what if it could let you feel subtle textures, or had infinite resolution, or let you get inside the head of a character and experience their emotions—and the punchline is this tech was invented thousands of years ago and it’s called “text.” And I think because it engages your imagination so much, interactive metatext is just inherently delightful. The incredible Emily Short has a text game called Counterfeit Monkey set in a world where you can change objects by inserting or removing letters from them (the title refers to a clever con involving a “k-inserter”). It’s so fun to play, because your brain loves to try to visualize these situations that straddle the line between words as signs and the signifiers they represent.

It’s no accident that there’s a huge overlap between people who love authors like Borges and Calvino, and people who are into interactive fiction.

Your decision to present each of the featured games as a “touchstone”, rather than as monolithic or inevitable milestones, fits well with text games and their spirit of exploration. While this approach serves the book well, were there any particular chapters where the decision about which game to highlight was particularly difficult?

The book covers one game from each year between 1971 and 2020, and choosing the set of games was definitely a terrifically complicated juggling act. I had spreadsheets!

There were a lot of styles of game I wanted to cover, but I also wanted to include games by a range of different kinds of people. I wanted a mixture of famous games and little-known gems, epic games and micro-games, some games noteworthy for their writing and some for their systems, and some just for their cultural impact. I wanted to hit certain famous authors and famous design systems, and touch on big shifts in hardware, like the rise of mobiles and tablets as a platform for interactive stories in the 2010s. So it was a huge balancing act to try to find a set of fifty games that covered all these angles, while all being interesting in and of themselves to write about. I had to leave out many personal favorites, which was sad, but it also did make me embrace the spirit of the project a little better, as you pointed out: it forced the book to be not the best or most definitive games, but just one possible tour through the space of this genre, out of many.

The book’s final chapter covers Latitude’s AI Dungeon. Videogames have had randomized and procedurally generated aspects since their earliest days (both in code-based backends and user-facing narratives) but the current moment does feel like a crossroads for games and society at large. Your description of the current state of AI as a “fire” is especially fitting—a tool or aid if controlled, a destructive force if left unchecked. While it’s too early to say which will be the case, would you describe yourself as optimistic or pessimistic when it comes to the opportunities and dangers present in generative language models?

I think like any disruptive technology, it’s going to be wonderful and terrible, and more wonderful and more terrible than we can really imagine right now. I think a lot about the invention of the automobile, which opened up huge amounts of freedom to many more people, while also having massively detrimental effects to the environment, the design of cities, and many other things. With AI, at times I feel very hopeful about the way these new technologies are going to empower writers and storytellers, but it also seems pretty clear it’s not going to come without a cost.

I do feel sure that there will be a next fifty years of text games, and another after that. People have been using language to tell stories for thousands of years, always enthusiastically embracing whatever new tools are invented to help them do that, from papyrus to ballpoint pens to typewriters to large language models. I don’t think that desire is going to go away, no matter how many AI storytellers are available at the touch of a button.

Any ideas for next projects, or are you completely focused on the current book launch?

I’ve been in non-fiction mode for a number of years now, so I’m really jonesing to get back to fiction and game design. I released a novel in 2020 with some generative text components, and have been doing some tabletop roleplaying books here and there too, but it would be really fun to write another interactive fiction game or two.

Lastly, what games are you currently playing, whether new or old? Any text games released post-2020 that you’ve found especially interesting?

I’ve been playing Failbetter’s Mask of the Rose, which is a delightful story-centered game in the Fallen London universe, and enjoying it immensely. Before that, I was working through games entered in this year’s Spring Thing, which is an online festival of new interactive fiction that I organized for almost a decade before passing the torch on this past year (and a great place to see what kinds of text games people are currently writing and reading). Thank god the book ends with 2020, though, so I don’t feel obligated to have a definitive answer! 😉

Physical copies of 50 Years of Text Games are sold out, but the book remains available as a multi-format e-book. Learn more about Aaron’s books, games, and other projects on his website.